Coral Reef Restoration

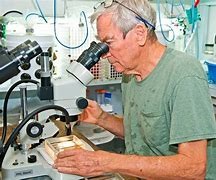

Martin Moe

We all very much want to restore coral reefs. We want to restore them in every place where they currently exist and are trying to maintain that existence, and where they have recently existed. It would be wonderful if we could do that, but at this point that can’t be done. However, we have done some great things in last few decades toward making restoration possible. We have learned how to cultivate many species of corals in various areas of the world. We have learned how to find, select, and propagate genotypes of corals resilient to destructive changes on coral reefs and have begun efforts to replace these genotypes on dying coral reefs. We have studied the role of symbiotic algae essential to the life of corals, propagated these essential symbionts and are finding ways to use them to enhance coral propagation. We have been able, at least up to this point, to keep a number of coral species in existence and even to replace them on our dying reefs with some short-term survival success. Note that successful establishment of corals on the remnants of coral reefs should be measured in decades and not just years, but months and years are a measure of some initial success.

We are in the process of learning how to control environmental conditions in captive aquatic environments that stimulate corals to spawn in captivity and then rear these corals through larval, settlement, and early juvenile existence. Interestingly, we have found that the presence of juvenile sea urchins enhances the early survival of juvenile corals. And over the last three decades we have learned on a large but amateur hobbyist basis how to maintain and grow corals in small aquarium systems. For the Caribbean, Florida and the Bahamas, where the function of herbivory is primarily accomplished by Diadema sea urchins whose presence on Atlantic coral reefs extends back well into the Pleistocene epoch. The herbivory from Diadema was essential to the health and growth of coral reefs right up to plague 1984 which eliminated the keystone herbivore of this extensive oceanic area. It is now possible to spawn on demand and rear Diadema sea urchins in large numbers. The Florida Aquarium Center For Conservation is now developing this capability. Thus, the capability of returning the function of herbivory to the coral reefs of this great area is now conceivable.

But this is not nearly enough. Corals are only one of the keystone species that make up the ecosystems of coral reefs. It is the coral reef ecosystems that must be restored on a permanent basis before coral reefs can once again flourish in tropical waters of planet Earth. We may not be able to do this. If we cannot accomplish this, then we probably also won’t be able to restore and preserve the terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems of our planet in a way that will provide for the continued civil and technical advancement of humanity. There are huge and difficult tasks ahead of us in order to restore and maintain healthy coral reef ecosystems. Corals are plagued with disease and loss of intracellular algae symbionts essential to the nutrition of coral polyps (bleaching). Water temperature increase causes the coral polyps to eject their algal symbionts which causes death of coral tissue if the algae cannot be restored to the coral tissue. Primarily bacterial coral diseases are often pandemic and responsible for extensive coral death on affected reefs. These conditions have been extensively researched and are now better understood by science, but oceanic environments prevent effective treatments and entire species of certain corals are in danger of extinction.

Some of us have no clue as to the severity of the problem, some of us, like the little train engine that could, are valiantly pushing humanity up the hill of attaining ecosystem repair and stability with everything possible to us at this time; and some of us see no hope, have thrown in the towel and see no pathway to the possibility that humanity can repair itself and its environment. I lean in that direction.

But for the sake of our future, we must try to fix the environment without entertaining the possibility of failure. The first airplane was invented in 1903, only 120 years ago… and now we fill Earth’s atmosphere with aircraft beyond number, 12 humans have walked on the moon between 1968 and 1972, and we have flown a miniature helicopter (with the capability of retrieving it) on the planet Mars. Are our marine environments of any less value to humanity than exploration of environments beyond our Earth?

The most important task that we absolutely must accomplish, even before we figure out how to limit the growth of human populations on our planet, is to remove, somehow, someway, the incredible and increasing quantity and composition of chemical waste in fresh waters, marine waters, and terrestrial environments. This includes not only fossil fuel emissions but also pollutants generated from agriculture, and physical and liquid waste discharge. This is not new news, far from it, but I mention it because it is a foundational issue. Without the reduction/removal/control of the waste that humanity produces, other efforts at ecosystem protection are moot. And not only do we not know what chemicals are present at what concentrations at various time in our marine environments; we do not know what effects many of these chemicals may have on planktonic and larval forms of marine life. It may not be too late to rescue our ecosystems from chemical pollutants, but that window is rapidly closing. Climate change must also be addressed. We are working on changing the capacity of corals to withstand increasing water temperatures, and that may be helpful in coral restoration efforts if the causes of climate change can be addressed. However, the goal must be reduction of atmospheric carbon dioxide, otherwise the ecosystems of our planet will no longer be supportive to human occupation.

When it comes to coral reefs…. we must assume that restoration of coral reef ecosystems to any shadow of what existed in the early years of the 19th century just isn’t going to happen by itself. But it will take time and we don’t have much of that. There are two things that can be done, and that have a chance of buying time and aiding us with the preservation and potential restoration of coral reefs. For restoration to be effective in the future, it is the entire ecosystem that supports coral reefs that must be preserved as best as is possible. What do you think the chances are that within the next 30 years humanity will have repaired the marine ecosystems that can establish and support coral reefs resembling those of, say, 1960, although 1860 would be much better? Would that be an 80% chance, or 50%? Maybe only 20%, possibly 10%, or less? Maybe in the next 100 years coral reefs will again shelter shorelines from storms and be once again wonderous environments created and maintained by marine organisms in a functional marine ecosystem. Whatever a realistic chance of this happing might be, it won’t happen by itself. Humanity must repair the ecological damage that is occurring now.

Spreading coral fragments over large areas and hoping for ecosystem restoration is commendable but without ecosystem repair, this has questionable chances for long term success. This is not to say that this should not be done. Small success can become great success and we will learn much about repair of coral reefs from this activity. However, we would also learn a great deal about coral reef restoration through another approach developed simultaneously. There would be two interactive parts to this initiative.

We have established areas, National Sanctuaries, where coral reefs are protected from exploitation, and this is very good, but we can take this a step further. We could select smaller areas of decaying coral reefs that can be established as “coral reef educational and experimental preserves” where the object is not only replacement of basic coral species but also includes reestablishment and monitoring of functional coral reef keystone species including herbivores, certain alga such as coralline algae, some sponges, some crabs, even some reef fish, and other organisms that are functional in coral reef ecosystems. These preserves would be cooperatively maintained and operated by governmental and educational institutions. The difference between these and existing sanctuaries would be the intensive, continued, and fully fiscally supported permanent activity aimed at ecosystem research and restoration contained in a manageable and well-defined area. Coral diseases will be better able to research and experiment with control in a limited area that is subject to frequent and detailed examination by experienced and knowledgeable personnel.

The second arm of such a project would be the establishment of a totally controlled, relatively large establishment of a land-based endeavor that would strive to create a contained coral reef ecosystem where control of chemical, physical, and biological elements are prioritized, rather than emphasis on artistic displays. This would create not only a fully controllable marine reef environment, but also a “bank” of coral reef ecosystem controlling organisms and corals that could contain living coral species that are critically endangered in the wild for preservation and active research independent of the vagaries and environmental hazards that plague our existing and endangered coral reefs. There would be close cooperation between the experimental restoration of a natural coral reef and establishment of a synthetic, land based coral reef ecosystem.

Pie in the sky? Incredibly expensive? Questionably possible? Technically unknown and uncertain?

Yes, yes, yes, and yes!

Worth creating even if the “writing on the wall” on the future of coral reefs seems inevitable? In my opinion. Yes!

Martin Moe